MFA Sites:

Why They’re So Hard to Define, and Why That Doesn’t Matter

Made For Advertising sites (or MFA sites) have had a resurgence in the latest news cycle, thanks to two key studies that came out recently:

- Made for Advertising (MFA) websites comprise a startling 21 percent of study impressions and 15 percent of spend.

- Did Google mislead advertisers about TrueView skippable in-stream ads for the past three years?

These in-depth investigations bring much-needed visibility to the topic of inventory quality. The bad news?

None of this is new.

The earliest reference to MFA sites I could find was from… drumroll…. 2004. Back then, MFA stood for Made for Adsense.

Other pseudonyms used over the years to describe this kind of inventory include ad farms, ad arbitrage, or just plain ol’ junk.

While the name, along with the tactics used, has evolved, unfortunately, the solutions have not. Nor have we come any closer to solving this “MFA/junk inventory problem” nearly 20 years later.

Why haven’t we solved this issue?

Because we’re too busy battling with five disagreements.

1. Disagreement on the definition of MFA

What defines a “made for advertising” website?

Ask 10 marketers, you’ll get 10 different answers. Conceptually, a made for advertising website simply has too many ads and not enough content. But:

- How many ads qualify as “too many”?

- What is “not enough content”?

- Does the quality and originality of the content matter?

- Do we include things like how the site sources its traffic?

And lastly, the unspoken question about MFA sites that highlights one of its major flaws: does the site’s traffic rank matter?

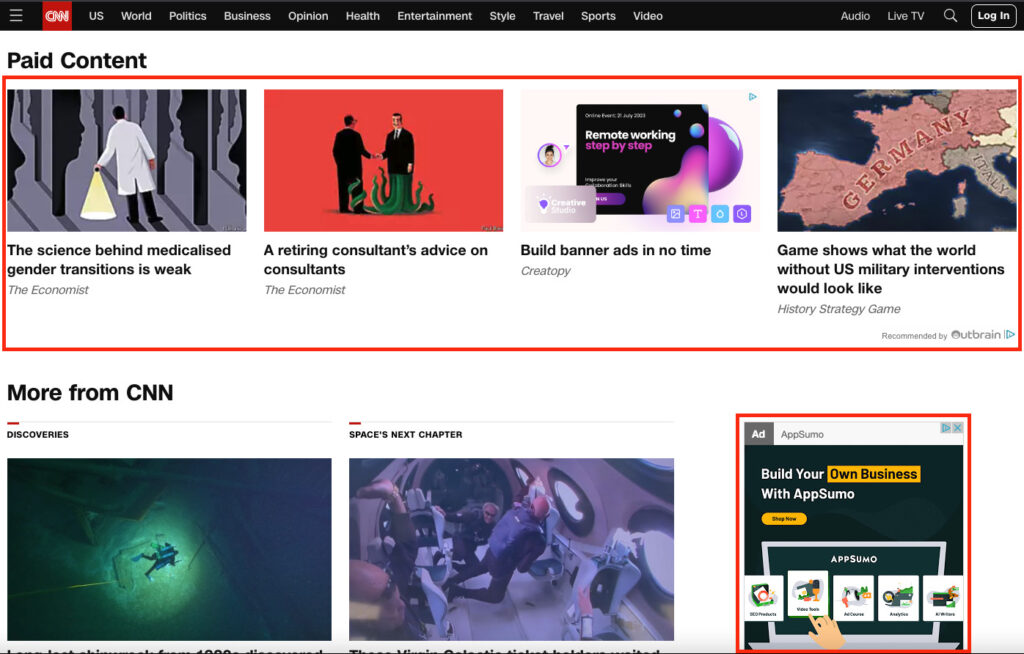

MFA sites tend to single out the long-tail, no-name sites. But what about some of the biggest sites we all go to that are just as bad?

2. Who is responsible for putting an end to MFA sites?

Is it the publishers that create them? Is it the advertisers that spend their ad dollars there? Is it the adtech players in-between that make it all possible?

Much of the rhetoric focuses on the MFA publishers.

And why not? These anonymous publishers make for great adtech boogeymen that we can point to and say THEY’RE our problem! They’re the bad actors making these terrible sites.

Everyone loves a common villain. Just read this WTF are MFA sites? from Digiday:

What’s deceptive, fueled by profit and involved in ad arbitrage? Made-for-advertising (MFA) sites. These cunning sites masquerade as prime real estate for online advertising, luring gullible advertisers into their web of trickery.

With each passing day, their misleading practices grow more refined, perpetuating a lucrative grift that shows no signs of abating.

And it’s easy to just get a blocklist of 100 or 1000 of these sites and call it a day, move on to the latest crisis, having solved this one.

3. Then why does the problem persist?

Block lists/blacklists/deny lists are a game of whack-a-mole. For every site you block, 10 more pop up in its place.

It’s easy to spin these sites up, and with AI, it’s only getting easier:

Another question Digiday poses (and answers) in its article:

So this is really another way programmatic advertising is being gamed?

Yes, that’s the crux of the issue.

I would argue nothing is being gamed here; the game is being played as it was designed.

If advertisers give publishers points for viewability scores, why wouldn’t publishers cram their site with a bunch of “viewable” ads above the fold?

The real crux of the issue: buyers are signaling to publishers that this is desirable inventory.

Why do buyers love this inventory?

- It’s cheap.

- It’s “viewable.”

- It “drives conversions.”

The “it’s cheap” angle is getting the majority of the coverage as the reason MFA inventory persists. However, the real problem is our addiction to numbers 2 and 3.

The very definition of viewability should already raise some eyebrows. It is not whether an ad is seen, it is whether the ad has the “opportunity” to be seen.

Did I have the opportunity to become an Emmy-award-winning actor? Sure. Doesn’t mean it was likely.

If only half of a display ad is on screen for one total second, it counts as viewable.

Did it have the opportunity to be viewed? Sure. Doesn’t mean it was likely.

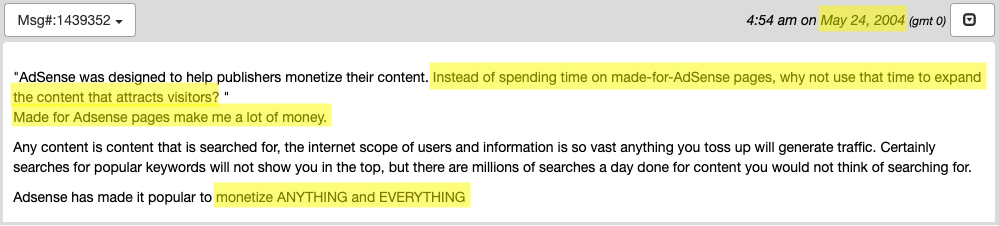

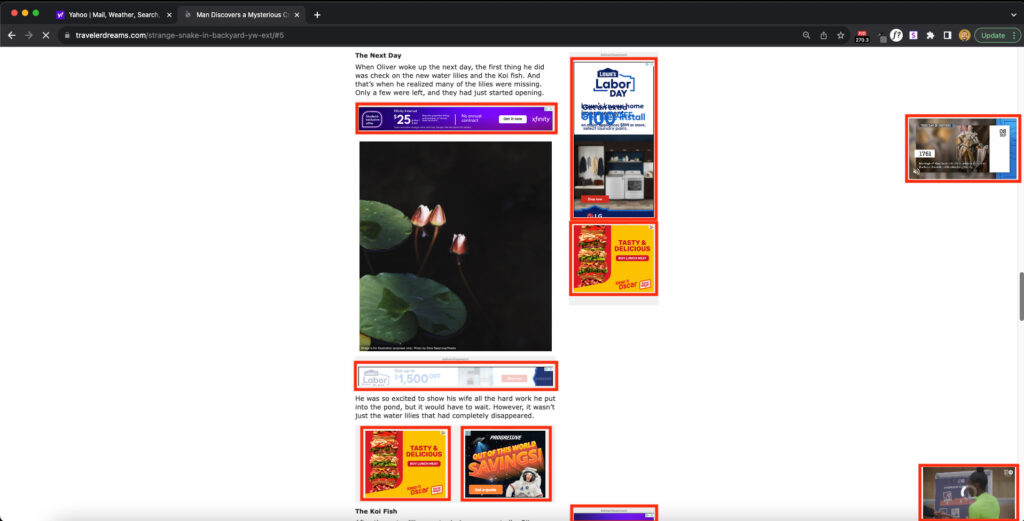

Or, the flip side of the ad barely being on screen is 8 ads all being on screen at the same time. All count as viewable.

You find these placements on MFA sites all the time to goose up that viewability score. Ever seen 4 TV commercials playing on screen at the same time? Didn’t think so.

Can unseen ads be effective?

If the ads are barely seen, or not seen at all, how could they possibly be driving conversions? Well, they’re not.

But in digital advertising, advertisers commonly apply “view-through” credit. The principle behind view-through attribution is that advertising doesn’t always have an immediate impact.

If your message resonates with the audience, you hope that at some later point, when they’re ready to make a purchase, they choose your brand.

This is the right idea. However, view-through credit gives no consideration to the quality of the impression.

Was it even on-screen, let alone seen?

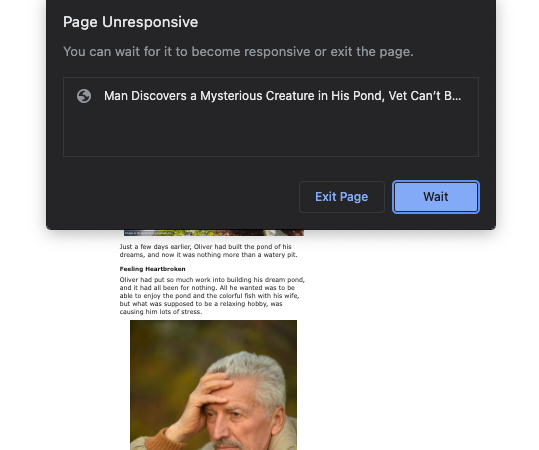

Was the interaction with the user positive, or was the ad one of 8 on screen for one second before the frustrated user hit the back button on their browser?

4. Disagreement whether the problem needs to be fixed

This section may ruffle a few feathers. But the adtech industrial complex is financially incentivized to not fix the problem.

If you spend money with an agency or a DSP, they want to show you that the ads are working so that you spend more money with them.

And what better way than to tie your ad spend to real, tangible conversions for your business? That is the benefit of digital over traditional media, right?

But many/most of these conversions would have happened anyway.

It’s the equivalent of a company handing out flyers to customers as they walk in the door, and then claiming credit for those customers.

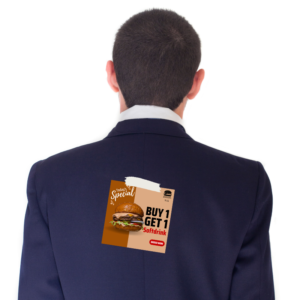

No, actually, worse than that. Because many “view-through conversions” were from ads that were never actually viewed.

So really, it’s the equivalent of slapping the flyer on the customer’s back unknowingly as they walk in.

But, tying more conversions to ad spend allows the CMO to tout that, yes, they spent $1M on ads, but they drove $2.5M in Sales.

Pretty nice return on ad spend (ROAS). Just don’t ask the CMO how many of those sales would have happened anyway.

Spray-and-pray

There’s a reason the term “spray-and-pray” exists. It’s also the reason that if you visit Zappos.com and leave some shoes in your shopping cart, you will get hit with Zappos ads until the end of time.

Every ad vendor the agency works with relentlessly buys up these retargeting impressions.

Users think Zappos is hounding them with ads. In reality, it’s 10 different DSPs and ad networks hounding them with the ads.

And it’s not because these vendors want to drive the user back to complete their purchase. It’s because they want to get CREDIT for doing so.

So, if the inventory is cheap, it’s “viewable,” and it drove “view-through conversions,” why do we need to get rid of it?

5. Disagreement around how to fix the problem

For those who acknowledge poor inventory quality is a problem and needs to be fixed, congrats on making it this far. But, how should you tackle this challenge?

Some are taking the block list approach.

This is better than nothing, but we already discussed some limitations of this tactic. If we can’t easily define what an MFA site is, and new ones pop up all the time, then it will be a constant battle.

Others are taking the inclusion list approach.

This gives much tighter control over where your ads run. But limitations exist here as well. Manually reviewing thousands of sites (and not just the homepages, but a thorough analysis of the entire site) is not feasible for most.

Site lists often stick to the same top 500 or top 1000 sites, missing out on hidden gems that connect with valuable audiences.

Many lists lack support for underrepresented sites, including Black-owned and LGBTQ+ platforms, which bring diverse and unique perspectives often overlooked in manually curated lists.

Lastly, inclusion lists give the benefit of the doubt to all of the largest sites.

However, we commonly encounter terrible user experiences on well-known sites that load the user up with ads and bog down the site’s load time and navigability.

Solutions to Consider

The digital ad game is being played as designed. And that design is broken.

If you are a brand, or work with brands, and agree that:

- 10 small ads on-screen will not have the same impact as 1 large ad on-screen, and

- Your digital ad strategy shouldn’t rely on slapping flyers onto customers’ backs

Then: don’t rely on viewability as a proxy for quality, and view-through conversions as a proxy for performance.

Don’t keep playing the same digital ad game over and over and hoping for different results.

With changes in privacy standards and regulations, user consent, and third-party cookies, now is the best time to take a new approach.

Some ideas to look at if you haven’t before:

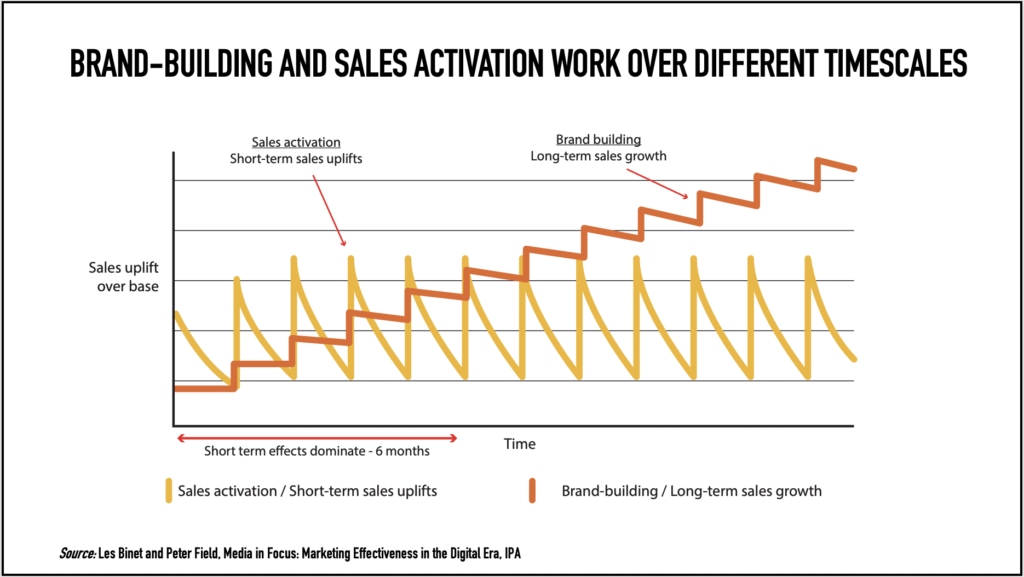

- Long-term metrics. Digital advertising isn’t solely a short-term game, despite how it has been painted. How are you moving the needle over time? Consider incorporating metrics such as share of search.

- Incrementality tests. There’s a reason why your ad vendor doesn’t like control tests and rotating in blank banners to assess lift. One common test is holding out spend from a handful of markets and comparing lift.

- Let go of the “scale at all costs” notion. We have become too accustomed to needing maximum reach, and shied away from any changes that jeopardize “reach.”

- Acknowledge that not all ad placements are created equal. Programmatic advertising has treated inventory like a commodity, and it’s only about the audience. Try to break this mindset.

- Only then can you really consider an inventory curation approach. Despite the challenges with inclusion lists, that’s our recommended approach.

How to build an inclusion list

We discussed the limitations of only going with 500-1000 well-known sites, but this marks a fine starting point.

Then you can hone this list over time, where you add those hidden gems, and even cut those big-name sites that don’t have the experience your potential users love.

Given the challenge of defining “MFA” and then assessing this criteria across thousands of sites, you may want to look for ways to take a data-backed approach.

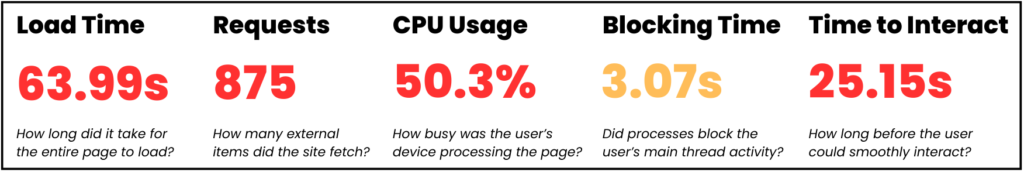

We are big believers in the value of user experience metrics. Indicators that tell you how fast a site loads, how many third-party requests it makes, how long until the user can interact with the page (scrolling, clicking), etc.

And here’s why we love user experience metrics: the sites stuffed with ads perform terribly on these metrics.

So, user experience metrics catch not only the MFA sites, but also the larger sites that have terrible ad experiences that aren’t effective uses of ad dollars.

Where to from here?

It’s great that MFA sites and inventory quality are getting some overdue attention.

But just talking about it isn’t gonna cut it.

Many misinterpret addressing the MFA issue as a moral choice: if I want to “do the right thing” and cut out these sites, I’m doing it solely for feel-good reasons, and at the expense of decreased scale and performance.

The realization we need to agree on: cutting this inventory is not a trade-off.

These sites are bad for users AND bad for brands.

How will users feel towards the brands advertising here?

What is an MFA site, and what isn’t?

Honestly, it doesn’t matter, because the problem is bigger than just a handful of MFA sites.

Can consumers really be receptive to your brand’s message when your ad is sandwiched on-screen with 7 others on a slow and frustrating site?

The legacy metrics everyone is hooked on will tell you these ads are working.

Only once we acknowledge the entire digital approach is broken, can we move on to step 2: what should we do about it?